KST, PMAX, MIE… What Does It All Mean for Your Combustible Dust?

There are many things that can affect the hazard that your combustible dust presents. It’s possible for dust that is very safe under most circumstances to cause a dangerous explosion if something goes wrong. Here we’ll talk about some of the kinds of information that you may need to know about your dust to make sure you are protected.

Many engineers will recommend that you test your dust professionally before finalizing your system design. There are a variety of companies that do this; check with your systems engineer to find out who they prefer to work with. This will require you to send in a sample of your dust. If you have more than one type of dust (for example, fine dust from welding and heavier rough dust from grinding), you will want to send samples of all of them to make sure your system can be designed for maximum safety. Combustible dust explosions kill people every year and cause massive damage to property, and it’s worth controlling the problem safely in your facility.

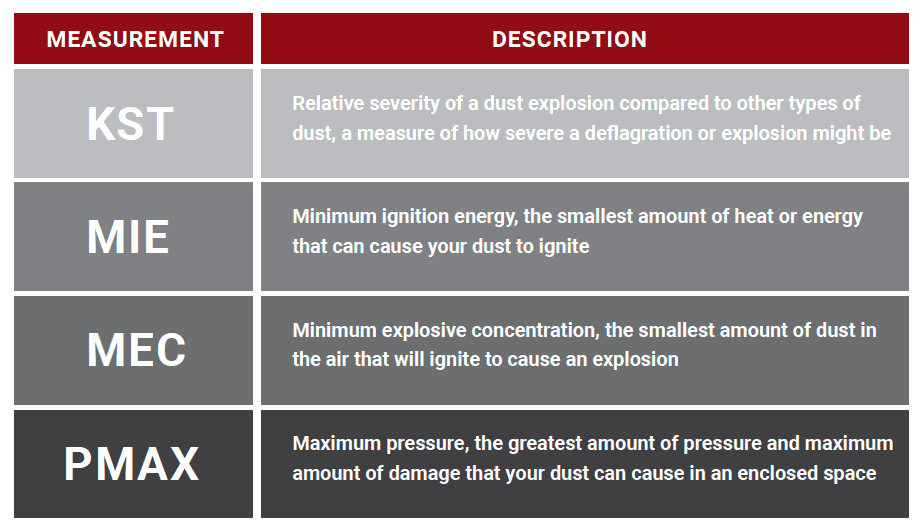

Dust Test Measurements

PARTICLE SIZE (microns):

Some materials are very inert as large pieces, but will burn rapidly in small particulate. Particle size measurement is usually in microns. This is also important for filter efficiency. Particle size is also very important for health purposes: larger particles may be trapped in the nose and throat where they are easy for the body to get rid of, while fine particles (under 30 microns) travel deep into the lungs.

MINIMUM IGNITION ENERGY (MIE):

This is a measurement of how much energy your dust requires to ignite. Some dust requires a lot of energy to ignite (in some explosions, the source of ignition has been an overheating bearing or an open flame). Other dust can ignite with much less energy. Static charges can ignite many types of dust. MIE is how much energy the dust needs to make it ignite.

MINIMUM EXPLOSIVE CONCENTRATION (MEC):

This measures how much dust must be present to cause an explosion. This measurement is usually with airborne dust. It tells you how much dust in the air will ignite if there is a heat source around. This is important because it explains how much dust needs to be floating around in the air to cause an explosion. A secondary explosion, which happens when dust that accumulates in the area lofts into the air by the first explosion, can involve a lot more dust and be a lot more dangerous.

MINIMUM AND MAXIMUM EXPLOSION PRESSURE (PMINand PMAX):

The minimum and maximum explosion pressure. Personnel conduct tests on dust inside a container that can measure pressure. Pminis the smallest amount of pressure that ignition of the dust can produce. Then there’s Pmax, which is more important. It is the maximum amount of pressure that explosive ignition can produce.

Pmax is measured by increasing the concentration of dust inside the closed chamber and measuring the pressure of the explosion until the maximum is reached (until the greatest possible amount of damage has been determined). This is an important calculation because it allows you to calculate how much damage your dust is capable of doing inside a closed container (like ductwork or a dust collector).

MAXIMUM RATE OF PRESSURE RISE/DEFLAGRATION INDEX ( KST):

MAXIMUM RATE OF PRESSURE RISE/DEFLAGRATION INDEX ( KST):

This measurement is done in a similar way to Pmax. A mathematical formula converts Pmax to KST, taking the volume (size of the chamber) out of the measurement.

KST is an extremely important test! The Pmaxmeasures the maximum pressure that the dust could exert exploding in a closed space, but KST is a general measurement of explosiveness. It is a standard measurement for dust collection system design purposes.

The Importance of KST

KST is a measurement of explosion pressure, NOT of combustibility. A low KST does NOT mean that your dust cannot burn and cause catastrophic damage. KST only tells you how strong the potential explosive force, not how flammable the dust is.

A KST of 0 means that dust is not combustible; its Pmin and Pmax are 0 and in a testing chamber it cannot produce any explosion.

A KST of greater than 0 means the dust is combustible; testing Pmax can create an explosion in the testing chamber. From 0 to 200 (which includes many metal dusts) the explosion class is 1; a weak explosion. NOTE: a “weak explosion” does not mean “no damage”! The catastrophic Imperial Sugar explosion that destroyed a building and killed over a dozen people was caused by sugar with a KST of 1.

A KST from 200 to 300 is a strong explosion (Class 2), and could include things like cellulose dust, other organic fine dust, and some metals and plastics.

A KST over 300 is a very strong explosion (Class 3). Aluminum and magnesium dust are in this category.

Any dust with any Kst above zero is potentially combustible and can cause an explosion. Your system will require appropriate fire and explosion prevention. Fire prevention is key to keep ignition sources out of the dust collector, including spark traps, abort gates, and water or chemical suppression systems. Explosion vent panels are also critical to make sure that an explosion does not cause serious damage if it does occur.

Dust Testing: Putting the Pieces Together

As you can see, all of these pieces of information are important when testing your dust.

– The KST (which is calculated from PMax) tells you how strong an explosion is likely to be.

– The size of the dust is important in determining whether it is combustible.

– The MIE tells you how much or how little energy it will take to ignite your dust

– The MEC tells you how much dust in the air will risk an explosion

A dust with a low KST (sugar, as an example, but also many metals) has a low but not zero KST. It is not going to cause a strong explosion. However, in one facility that had a lot of accumulated sugar dust, an overheating piece of equipment exceeded the dust’s MIE value and ignited it. With so much sugar in the air, the MEC was also exceeded and the dust in the air ignited explosively.

To review: in this instance, a dust with a LOW KST (sugar) was in contact with a heat source that exceeded the MIE and ignited the dust. Because there was a large amount of dust in the air, the MEC was too high and the dust exploded. Secondary explosions caused even more damage because the explosions blew dust into the air and raised the MEC even more. For more information on this incident, see the Chemical Safety Board’s report of the Imperial Sugar Explosions.

While this explosion did not have a high pressure, it did create multiple large low-pressure explosions that blew apart the building and caused numerous deaths. A low KST does not mean your facility is safe from combustible dust explosions.

Table 1: Key Terms and Definitions

Article featured in the July/August Issue of Shop Floor Lasers. Go here to see the digital issue. SHOP FLOOR LASERS

Read our white paper on combustible dust.

Read more